If you want to check out Slamdance for yourself, you can subscribe to their online channel for one month at $7.99 and gain access to the entire 2023 festival lineup from January 23 to 29. This is a steal considering you get access to dozens of features and shorts at the fraction of the price of one virtual ticket at Sundance or TIFF.

A small disclaimer: I’m not the best person to go to for documentaries, or just contemporary docs. Having done several years of film programming and reviewing titles at festivals or upon general release, I’m too accustomed with a certain form of expositional documentary filmmaking that I’ve developed a strong allergy to. I like to blame this on Alex Gibney, who I can’t say is the root cause, but he sure loves to churn out this type of middlebrow gruel as much as possible. I tend to compare documentaries and horror movies similar in a business sense: cheap to make and with enough of a built in audience that you have a decent chance of making some money off of it. This also means a ton of these things get made, and a lot of them aren’t good.

That’s not to say I dislike documentaries altogether (my favourite film of 2022 is a documentary after all). I just know I have a low tolerance for them, and when I see certain tropes in the format I tend to run in the opposite direction. Luckily, not a lot of the Slamdance documentary titles I’ve seen (so far) have been difficult to watch, although they tend to hit a ceiling. Emily Kaye Allen’s Cisco Kid is a prime example of that, a perfectly fine documentary that I could only get on board with up to a point. Set in the ghost town of Cisco, Utah, it follows Eileen, who buys up some property and spends years trying to make a home for themselves in the largely abandoned area.

Allen takes a distanced approach for the most part, letting her camera sit back and observe Eileen as they go about fixing up their home or any of the other areas on the property in dire need of repair. We get a lot of nice shots of the desert landscape (it’s hard not to watch some shots, especially the ones involving trains, and not think about James Benning’s films), and Allen has a fascination with Eileen as a portrait of resiliency and rugged individualism. That’s kind of where the observations end, and as personable as Eileen is, they don’t make for a compelling enough subject over the short runtime. Others may find more to enjoy here, but even as the film jumps ahead in time and introduces some new elements (one being Cisco turning into a sort of tourist attraction as Eileen continues building and rebuilding on their land), Cisco Kid never changes gears from what it shows at the outset.

I’m surprised that Slamdance decided to program Sweetheart Deal and Motel Drive in the documentary strand together, considering they touch on similar subject matter in ways that make it easy to lump them together. Both films look at issues around poverty and drug abuse in America, with Sweetheart Deal using a vérité style while Motel Drive relies more on an expositional form with talking head interviews. Surprisingly, it’s Motel Drive and director Brendan Geraghty who handle the subject matter better despite his tendency to fall back on familiar modes of documentary filmmaking.

Sweetheart Deal focuses on four sex workers struggling with opioid addiction in Seattle, who all work on the notorious Aurora Avenue (type “Aurora Avenue” in Google and “Seattle” will likely show up as a suggested search). All four are friends with Laughn, a man who lives in a trailer and offers a shelter for different women, whether it’s a place to hide or a spot to detox for a few days. Laughn is not some nice guy though, as he openly admits he has sex with the women that visit him, tends to pick favourites, and eventually turns out to do some horrifying things.

Directors Elisa Levine and Gabriel Miller adhere to a humanist approach, meaning very little examination of political or social factors and more of an emphasis on the four women and their uphill battles. All of their stories are compelling in their own right, like the matter of fact Kristine, a welder who says she only fell into sex work because she was between jobs, or Krista, a former straight-A student who makes the biggest transformation out of all the film’s subjects. I can’t say I agree entirely with Sweetheart Deal’s choice to keep the focus on the subjects rather than take a macro view on the environment and circumstances they have to adapt to and survive. There’s an implication that these people rely on themselves or each other to escape from their situations, which conveniently ignores social and institutional failures that played a role in putting people like these women in such dire straits. That makes the film’s conclusion, a sentimental bit of closure and a happy ending for at least one of the subjects, somewhat awkward given everything that came before it.

Motel Drive makes an effort to contextualize its subjects as at the mercy of greater political and social forces, which is why it works better even when it veers into the same sentimental territory as Sweetheart Deal. The title refers to a stretch of motels in Fresno, California, which used to be a vibrant tourist spot in the ‘60s and now houses people struggling with poverty and drug addiction. Director Brendan Geraghty hones in on several subjects; the Shaw family, whose 11-year-old son Justin tries to finish school while his parents find sources of income; Dannie, a veteran with a dark past who also resides in one of the motels; the head of a community group dedicated to helping impoverished children in Fresno (a group which Justin is a part of); a doctor running a needle exchange program in the city to help drug addicts; and the local police chief, who gets elected as mayor within the film’s seven years of filming.

All of this coincides with the construction of California’s High-Speed Rail Project, which is supposed to reinvigorate Fresno but requires displacing the motel inhabitants, as the project intends to build through the area. Geraghty follows the Shaw family over the years as they benefit from relocation funds provided by the government, only to lose everything as the project languishes, the money runs out, and Justin’s father Jason relapses into his meth addiction. Geraghty’s longitudinal approach goes a long way in showing how the government helps and fails the Shaws, while the community group and needle exchange program highlight how people are trying to combat systemic issues on a ground level. It’s a healthy amount of perspective that makes the passage of time more tangible (compared to Sweetheart Deal’s limited focus), and the various developments over the years more harrowing.

Granted, Geraghty’s conventional direction holds his film back, and I’m not a fan of his desire to tie things with an optimistic bow at the end (the former sheriff, now mayor, talks about ending homelessness in Fresno, which sounds nice but amounts to watching his campaign speech). But given how much we see, like the inability of the state government to do its job, the massive deck stacked against people like the Shaws, and the people dedicated to offer some relief or assistance however they can, I can’t blame him for wanting to find something positive to hold on to.

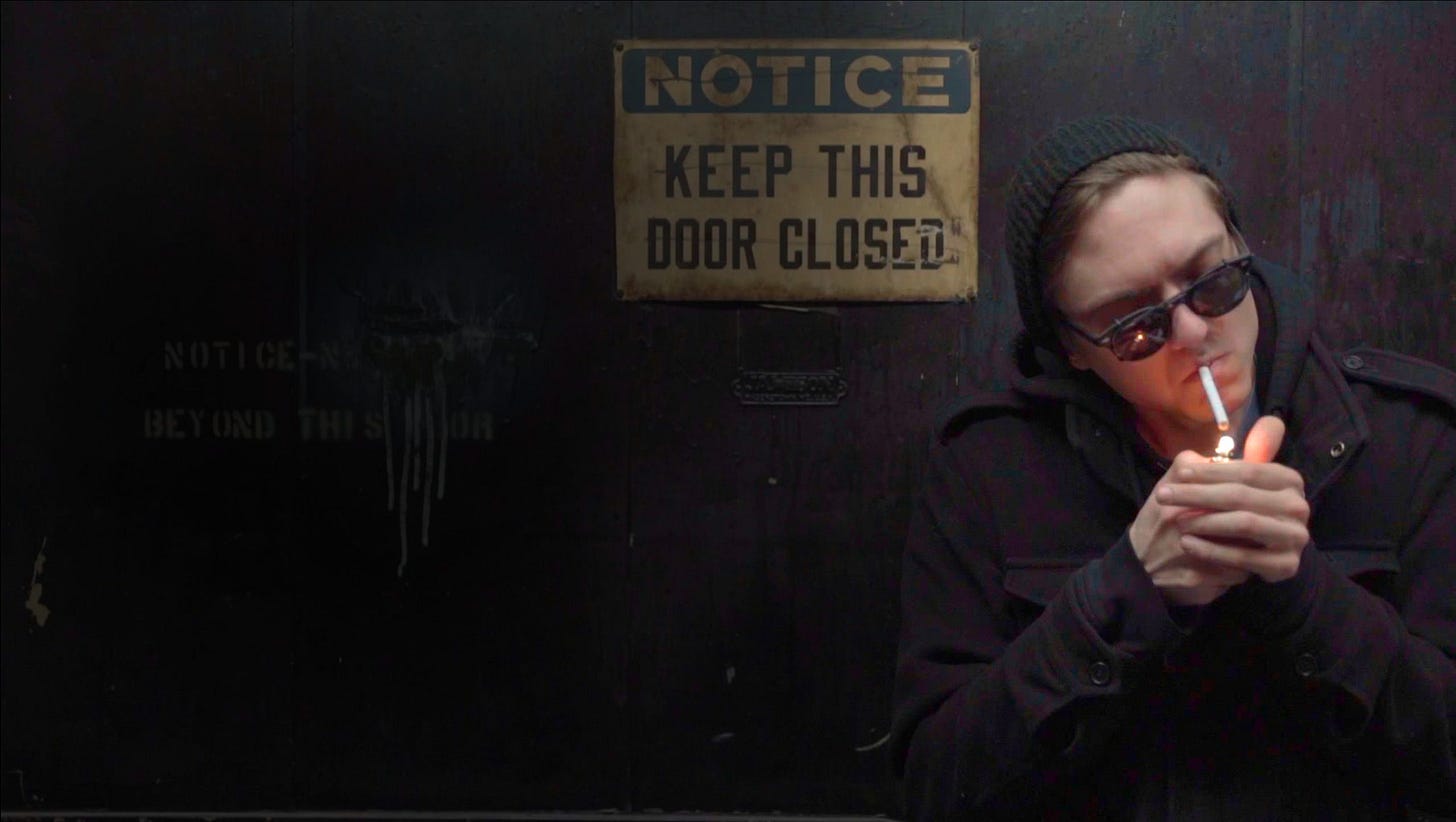

A much lower-key affair than the previous two films, Zack Kashkett’s The Mad Writer also relies on sentimentality and optimism but with the hook of a subject who doesn’t want any part of it. Kashkett asks his friend and music producer Austin, aka L’Orange, to be the subject of his documentary, and he agrees even though he’s openly hostile to the idea. L’Orange does a talking head interview on a set and spends most of his time sarcastically attacking Kashkett in the way that longtime friends do. L’Orange trusts his friend, but at the same time he’s anxious to hand control over how he’s seen to someone else.

That tension makes for an interesting experience, even though L’Orange is largely correct about his life not being that interesting in the first place. Kashkett focuses on L’Orange’s medical condition of tumours growing in one of his ears, requiring surgery that will likely result in going deaf in one ear. That sounds like the making of an interesting story, especially for someone whose life revolves around music, but L’Orange knows that and constantly downplays the situation. But in the end he’s sort of right; while it’s a major change in his life, it amounts to a detour in his career, which he jumps back into as soon as he recovers. I expected L’Orange’s sardonic personality to grate over time, but he’s self-aware and self-effacing enough that The Mad Writer makes for a fine, passable documentary.